|

Theodore Roosevelt: America has a big role to play in world affairs We've already seen that in the early 1900s President Theodore Roosevelt believed America should take a more active role in world affairs. Even before he was president, he took part in the Spanish- American War (1898). Later, as president, he pushed for the building of the Panama Canal. Both of those helped boost America's place among the nations of the world. Roosevelt wanted America to take on greater responsibilities. He said that when necessary, the U.S. should step in directly to help solve problems involving other countries in the Americas. His new policy was called the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. That sounds complicated, but it just means "The new idea that Roosevelt added to the Monroe Doctrine." |

|

|

The Monroe Doctrine was already a U.S. policy The Monroe Doctrine was a U.S. statement of foreign policy that dates back to the early 1800s. It stated that the U.S. would oppose any attempt by any European country to take control of any country in the Americas. (See the map on the right - "the Americas" means North America, Central America, the Caribbean Islands, and South America.) The Monroe Doctrine is named for President James Monroe, who first declared it as part of America's foreign policy. |

|

|

What did the Roosevelt Corollary add to the Monroe Doctrine? The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine added a new policy to the old policy. Simply put, it said the U.S. had the right to intervene (step in directly) to deal with serious problems involving countries in the Americas. Roosevelt had good intentions. At that time some countries in Central America, the Caribbean, and South America were not very well run. What if they owed money to a European country but could not pay it back? The European country might be tempted to go in with military force and just take over. Roosevelt did not want that sort of thing to happen. If anyone had to go into a country in the Americas with military force to deal with a serious problem, he said, it would be better if the U.S. did it. |

|

|

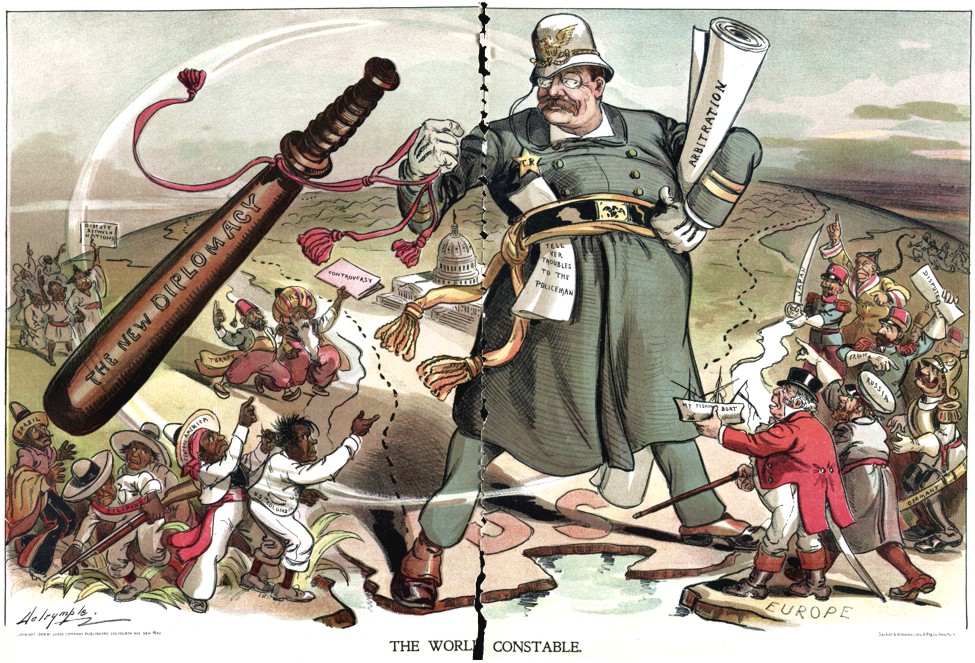

One

view of Roosevelt's foreign policy

The

political cartoon shown below appeared in an American magazine in

1905. It shows Roosevelt as wanting the

U.S. to become like a

"World Constable" or international policeman helping to settle disputes

among nations. (Constable

is an old word for a policeman.)

The cartoon makes a bit of fun of Roosevelt by showing him in an old fashioned policeman's uniform. The billy club is a reference to criticism that he had used "Big Stick Diplomacy" to get the Panama Canal project going. The artist probably wants readers to ask themselves, "Wait a minute, who gave Roosevelt or the U.S. the right to be the policeman for disputes between other countries?" The artist also gives another side of the issue, however. It shows that Roosevelt did have valid concerns. The countries of the world are constantly squabbling. The cartoon invites the reader to consider, "What would be the result if no country was willing to take on the role of a policeman, and help settle disputes among nations?" |

Click here to see this cartoon in a larger size.

|

How long did the Roosevelt Corollary last? The Roosevelt Corollary was used more than once by presidents in the early 1900s. At different times, the American military was sent into countries including Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua to try to deal with various problems. By the late 1920s, however, U.S. presidents were rejecting the Roosevelt Corollary as a bad idea that was making America look like a bully. American leaders began saying that the U.S. would not interfere in the affairs of other countries. The new emphasis in the 1930s was on working to form stronger friendships between the U.S. and other nations of the Americas. The new approach was often called the "Good Neighbor" policy. |

|

Photos and images are from the Library of Congress.

The maps are by David Burns.

Some have been edited or resized for this page.

|

Copyright Notice

Copyright 2009, 2017 by David Burns. All rights reserved. As a guide to the Virginia Standards of Learning, some pages necessarily include phrases or sentences from that document, which is available online from the Virginia Department of Education. The author's copyright extends to the original text and graphics, unique design and layout, and related material. |