|

As

settlers moved to the West,

conflict grew with Native Americans The drawing below shows a group of settlers headed west in 1869. The wagons are stopped for the night, and are pulled into a circle for protection in case of an Indian attack. Indians often resisted what they considered an invasion of their traditional hunting lands by settlers. Settlers said Indian tribes had no right to claim the millions of square miles of empty land in the West all for themselves. |

|

Indian

reservations were established

During the 1850s and 1860s, the American government began declaring specific areas of land in the West as Indian reservations. There were two main reasons for this: 1. To make more land available for settlers headed west. 2. To try to keep peace between Indians and the settlers. Most Indians opposed the idea of the reservations. While the reservations were large, they were not as large as the areas the tribes had roamed freely before. The government promised to provide the Indians with supplies of food and other help to encourage Indians to accept the reservation system. The old map below shows the reservations (orange colored areas) in the West as they were in the 1890s and early 1900s. The map is also labeled to show the areas where the various Indian tribes lived before the reservations were created. |

|

The Sioux

Reservation in South Dakota

The two photos below show a Sioux Indian reservation in South Dakota around 1890. The reservation system ended the old ways of following and hunting the buffalo herds. Instead, the government provided monthly deliveries of beef cattle and other supplies to the tribe. Government leaders hoped that over time the Indians would become settled farmers and cattle ranchers. |

Click here for a larger version of this photo

|

The

destruction

of the

great buffalo herds One big reason Indians of the Great Plains could not continue their free-roaming way of life was the destruction of the great buffalo herds. Indians of the Great Plains depended on the buffalo for food, and also needed the hides. Without the buffalo, their nomadic lifestyle of following the herds across the land could not last. American hunters in the 1870s and 1880s killed large numbers of buffalo for their hides. In some cases, the hunting was encouraged by U.S. Army leaders in the West. Army leaders wanted the buffalo herds reduced, since that would force Indian tribes to stay on reservations. |

|

Indians often resisted Westward expansion

and the reservation system

During the 1870s and 1880s, a number of battles were fought

as Indians in the West resisted the reservation system.

Here are four examples:

|

Geronimo - a

symbol

of resistance to reservations An Apache Indian leader named Geronimo became famous for his violent resistance to the reservation system and American expansion into the West. The Apache Indians lived in what is now Arizona and New Mexico. (See the map below.) Even before Americans moved into that area, raids by Mexicans against the Apaches, and by Apaches against Mexicans, were common. Geronimo's first wife and their children were killed in a Mexican army raid on an Apache village. When Americans began moving into the region, Geronimo and a small group of Apaches began attacking them. He refused to stay on the official Apache reservation. After many raids and escapes made his name famous nationwide, he finally surrendered to the American army in 1886. |

|

|

Sitting Bull

and the

Battle of Little Bighorn The most famous conflict involving the Sioux Indians was at the Little Bighorn River in Montana in 1876. The conflict began when gold was discovered on the Sioux reservation in South Dakota. Settlers - whites - moved onto the land without permission. When the government did not act to remove the settlers, some of the Sioux Indians left their reservation in anger. (See the map below.) Led by Sitting Bull, these Indians, along with some from other tribes, were in Montana in 1876. They camped along the Little Bighorn River, defying orders that they remain on their reservations. Soldiers from Fort Lincoln were sent to force the Indians back to their reservations. George Custer and about 200 soldiers under his command were badly outnumbered as they approached the Indian camp. He and all his men were surrounded and killed. It was a great - but only temporary - victory for the Indians. |

Sitting Bull, a Sioux Indian leader |

|

Custer and his

men were all killed

The newspaper drawing below shows George Custer and the soldiers under his command at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. The men were out on open land with no rock formations or trees to protect them from Indian gunfire. Custer was killed during the battle, along with all his men. |

|

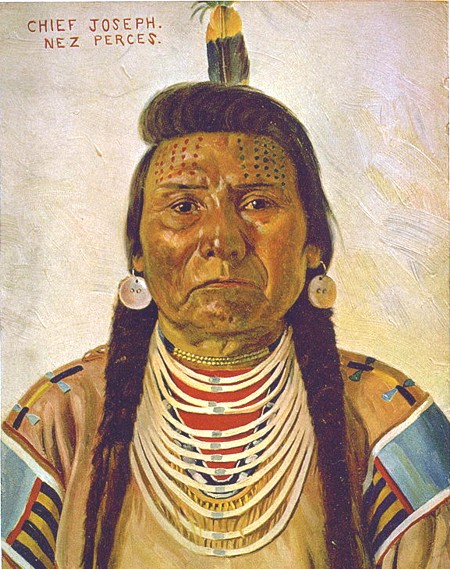

Chief

Joseph and the

Nez Perce reservation One of the saddest conflicts in the West during this period involved the Nez Perce Indians. The Nez Perce was known as a peaceful tribe. In the 1850s, the tribe made a treaty (an agreement) with the government about the size of its homeland. (The yellow area in the map below.) In the 1870s, however, the government wanted the Nez Perce to stay within the limits of a smaller area. (The green reservation area in the map below.) Most of the Nez Perce Indians agreed to do so. A group of about 800 Nez Perce Indians led by Chief Joseph, however, refused to accept the plan. As the dispute grew tense in 1877, four white settlers in the area were killed by Nez Perce Indians. The young warriors who did the killing acted on their own. Chief Joseph, however, knew the murders would probably bring trouble for everyone. He and his group decided to flee to safety in Canada. |

|

|

The path to

Canada

The map below shows the path of Chief's Joseph's group of Nez Perce Indians as they fled toward Canada. American soldiers were in pursuit every step of the way. The line is very crooked because that is the area of the Rocky Mountains. |

|

The top story

in the newspapers!

Americans all over the country were fascinated with the story of Chief Joseph. They eagerly followed newspaper reports as the army chased and battled Chief Joseph's group of Nez Perce Indians for three months. The Indians finally surrendered in Montana, not far from the Canadian border. This drawing is from a newspaper report. |

|

Chief Joseph's

famous words of

surrender

When he surrendered, Chief Joseph made a short statement to the commander of the American soldiers. His speech ended in these words, which have since become very famous: "From where the

sun now stands,

I will fight no more forever." |

|

The

Battle

of

Wounded Knee The pictures below show the Battle of Wounded Knee, also known as the Wounded Knee Massacre. Over 150 Sioux Indians were killed at the camp beside the Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. The Indians were being held there by soldiers in 1890 because army leaders believed the Indians might be preparing for a fight. Shooting at the camp started when a Sioux Indian resisted an agreement by the group to surrender their weapons. In a struggle with several soldiers, his gun fired. The shot turned the already tense situation into chaotic fighting and gun fire. Some soldiers, completely out of control, even shot some of the women and children who fled the scene. |

|

| The

photograph below shows the Sioux camp at Wounded Knee three weeks after

the massacre. A blizzard hit the area after the battle, and

delayed the burial of the dead. |

|

A place to

remember the past

The photo below shows the burial site of the Sioux Indians who were killed at Wounded Knee. A memorial stone now marks the location, which is a National Historic Landmark. A ceremony is held there each year in memory of those who died. |